One challenge in improving quality of life for patients and loved ones affected by KIF1A Associated Neurological Disorder (KAND) is that there are not always clear-cut answers for symptom management. Spasticity is a common KAND symptom, and while multiple treatments are available, the decision of which to use depends on each individual situation. To help inform your decision, we’ve collected some resources on treatments for spasticity that you can discuss with your doctor when making decisions about care. At the bottom of this page, you can also find a “KAND and Spasticity” presentation from Dr. Jennifer Bain and Dr. Jackie Montes of Columbia University.

How do muscular reflexes work?

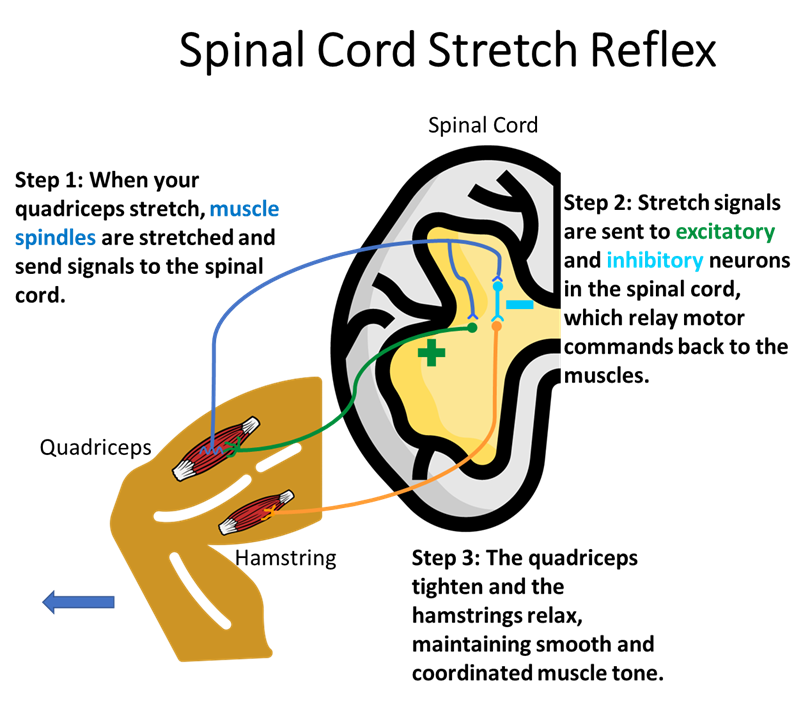

Muscles can be used to apply force in many fundamental parts of our lives. Some examples of muscle-produced force are pushing, pulling, and lifting objects. To do this smoothly and efficiently, muscles also need to resist forces that are applied to them: When your arm is pulled unexpectedly or something is heavier than expected, the bicep’s natural reaction is to tighten, or contract.

The muscles in our body also exist in pairs that work in opposite directions: When one muscle contracts, its partner relaxes just enough to maintain even muscle tone that creates smooth movement in both directions.

These reflexes are crucial to adapt to an ever-changing environment and to control our own movement, like walking. Below we’ve illustrated the neural machinery that drives these reflexes.

What is spasticity?

In spasticity, the muscle-spinal cord circuits are hyperactive. When a muscle is stretched, its signals are amplified to cause more intense contractions than necessary, which can override intentional movement originating in the brain. Spastic events are often velocity dependent, meaning the faster a limb is moving, the harsher the contraction, and this can cause feedback loops of spastic jerking during voluntary movement.

Spasticity can result from inhibitory signals that are too weak, or excitatory signals that are too strong. These signals can have an impact in the spinal cord or in the muscles. In either case this results in muscle rigidity and sudden, poorly controlled movement. The lack of coordination between muscles can also cause fatigue and pain.

Spasticity Interventions

Choosing therapies

Each case of KAND is different, and the choice of therapies to use in spasticity treatment is a personal one. When considering treatments consider the following:

- How much does the symptom impact quality of life, and what amount of improvement would make a meaningful impact? Ultimately, we want KAND patients to live happy lives. Spasticity is a broad term, but consider which aspects of movement are most important to improve when discussing with your doctor.

- How will the treatment impact quality of life? Treatment frequency, invasiveness, and reversibility can impact our day-to-day life almost as much as symptoms. Oral medications, local injections, spinal pumps, and one-time surgery all have different pros and cons to consider when determining the long-term viability of treatment.

- How do short-term benefits weigh against long-term side effects? KAND is a neurodegenerative disorder. Treatments that chronically reduce neuronal activity may interact with this degeneration to complicate long-term outcomes. For some patients and families, improving quality of life now is worth it in a disorder that is ultimately degenerative. Others may wish to wait on intervention, especially if symptoms are mild.

A common thread: Physical therapy and rehabilitation

Our nervous systems are built to adapt, and moving with spasticity is no exception. Because spasticity generates a lot of force, many people with KAND integrate spasms into their walking style. Taking muscle spasms out of the equation may cause more falls and fumbles because the patient is used to compensating for forceful movements that are suddenly absent.

For any spasticity intervention, physical therapy is a must: Just like training a skill like juggling, walking with less spasticity is a difficult skill that involves learning new habits and unlearning old ones. The more drastic the intervention the more important this is. Having a physical therapist involved before a new treatment is crucial, so they can understand the patient’s baseline and how to work with the benefits and side effects of a given interaction.

Stretching

Because spastic movement happens in response to limb extension, joints can become tighter over time, causing pain and limiting range of motion. Some clinicians recommend stretching to alleviate symptoms of spasticity. Long-term stretches are more likely to help: Spasticity depends on the speed of muscle movement, so keeping limbs stretched is less likely to cause contractions, while giving joints time to loosen up.

Administration

Passive stretches can be achieved through a routine prescribed by your therapist, or by the use of braces or casts that keep limbs extended for prolonged period of time. A patient’s ability to cope with short-term restricted movement is an important factor when considering the type of stretch therapy.

Potential Benefits

Stretching is a physical intervention that may help with range of motion, counteracting the tenseness brought on by spasticity. It can also be implemented in support of other interventions listed below.

Considerations

- Guidance: Stretching programs should be informed by a knowledgeable physical therapist to avoid improper extension that could be painful or further limit movement.

- Compliance: Whether engaging in exercises or using a brace, a patient’s ability to cooperate and cope with the program is crucial.

- Effectiveness: The benefits of passive or prolonged stretching for relieving spasticity are still being investigated, and may not translate to natural movements like walking.

Literature on Use and Benefits

The effectiveness of passive stretching in children with cerebral palsy: A review of studies on passive stretching for spasticity, outlining conflicting evidence of its benefits and differences between types of stretching interventions.

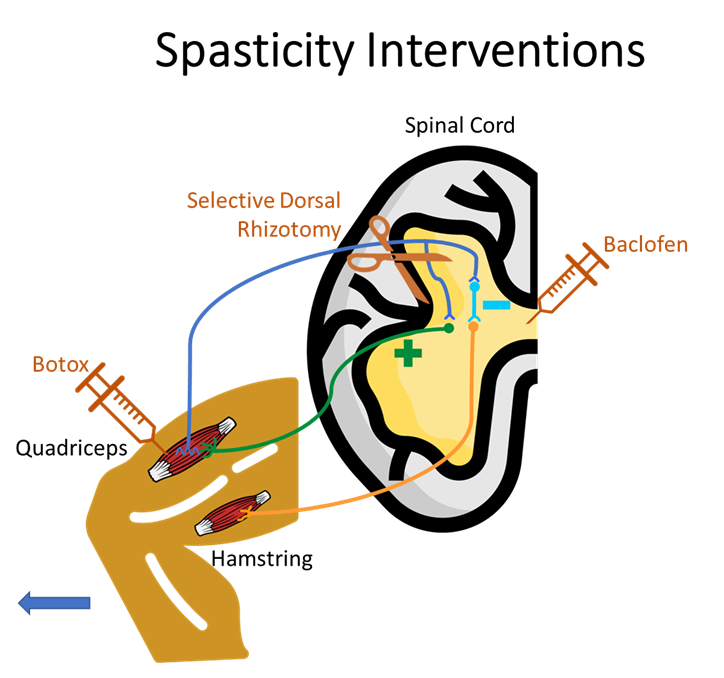

Baclofen

Baclofen is a skeletal muscle relaxant that acts on neurons that inhibit neuronal activity in the spinal cord, making muscular contractions less severe. It is commonly used to treat spasticity in multiple sclerosis or spinal cord injury.

Administration

Baclofen is usually administered orally or injected into the spinal cord through an installed pump known as intrathecal administration.

Baclofen does not readily bypass the blood-brain barrier, so oral doses tend to be much higher than intrathecal doses. Baclofen pumps require a surgical procedure and continued maintenance. In both cases, baclofen broadly impacts muscle groups throughout the body by acting on spinal cord neurons.

Potential Benefits

By decreasing the intensity of spinal-muscular reflexes, baclofen reduces muscle rigidity and the frequency of spasms. This results in smoother, more natural movement and can reduce pain.

Considerations

- Long-term muscle weakness: The nervous system adapts by strengthening commonly used circuits and weakening less-used circuits. Baclofen reduces neuronal activity between the spinal cord and muscle groups and these connections can weaken over time, decreasing muscle tone and strength. This is of particular concern for neurodegenerative disorders like KAND where circuits already progressively weaken.

- Drowsiness: As a molecule that increases inhibitory signaling, baclofen may make patients tired.

- Withdrawal: Because baclofen’s targets are so widely distributed in the nervous system, it is important to wean off of it gradually if stopping treatment. Sudden baclofen withdrawal can cause increased spasticity, seizures, and respiratory failure.

Literature on use and benefits

- MedlinePlus.gov Baclofen factsheet: An overview of Baclofen from the National Library of Medicine.

- Baclofen: Therapeutic Use and Potential of the Prototypic GABAB Receptor Agonist: A review of baclofen’s mechanism of action and use in spasticity and pain management.

- Intrathecal Versus Oral Baclofen: A Matched Cohort Study of Spasticity, Pain, Sleep, Fatigue, and Quality of Life: A comparison of intrathecal and oral baclofen efficacy over time.

- Quantifying the change of spasticity after intrathecal baclofen administration: A descriptive retrospective analysis: Characterization of intrathecal baclofen’s impact on spasticity as well as complications of intrathecal administration.

- Best practices for intrathecal baclofen therapy: Dosing and long-term management: A review of intrathecal baclofen dosing options and considerations for maintenance and care.

Literature on side effects and risk factors

- Encephalopathy and hypotonia due to baclofen toxicity in a patient with end-stage renal disease: A study on worsened baclofen side effects in patients with compromised kidney function.

- Oral Baclofen Withdrawal Resulting in Progressive Weakness and Sedation Requiring Intensive Care Admission: A case study of health impacts caused by a sudden stop in baclofen intake.

Botox

Botox, or botulinum toxin, is a chemical that reduces muscle spasticity by preventing release of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter sent from motor neurons to activate muscles. The result is less intense local muscle contractions. Other compounds such as Dysport work by similar mechanisms.

Administration

Because it acts on neuromuscular junctions, Botox is injected into specific muscle groups. This allows it to improve specific motor function even when spinal cord signals are hyperactive. This can reduce side effects and be useful for disorders where only some muscles suffer from spasticity.

Potential Benefits

Localized injections mean Botox treatments can be customized for each patient’s clinical needs: This can benefit heterogeneous patient populations like KAND, especially when both spasticity and hypotonia exist in different muscle groups.

Considerations

- Regular injections: Botox temporarily reduces neurotransmission and must be reapplied to maintain its effect, typically once every few months.

- Multiple injections: Because Botox is injected locally, patients with spasticity that impacts multiple muscle groups may require more injections during each treatment.

- Anesthesia may be needed: Patients must remain still while receiving Botox injections, and the injections can be uncomfortable for some patients. Because of this, some patients (especially children) may require sedation with anesthesia, which has its own risks, benefits, and side effects.

- Spread from injection site: “Postmarketing reports indicate that the effects of Botox and all botulinum toxin products may spread from the area of injection to produce symptoms consistent with botulinum toxin effects… In unapproved uses, including spasticity in children, and in approved indications, cases of spread of effect have been reported at doses comparable to those used to treat cervical dystonia and upper limb spasticity and at lower doses.” -Botox boxed safety sheet

Literature on use and benefits

- The Use of Botulinum Toxin for Treatment of Spasticity: A review of how Botox reduces spasticity but may have variable effects on voluntary movement, and considerations on improving efficacy.

- Efficacy of a Combined Treatment of Botulinum Toxin and Intensive Physiotherapy in Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia: Botox injection in hamstrings and quadriceps, in conjunction with 20 hours of physiotherapy focused on posture and gait training improved walking in a study of 18 people.

- Health-Related Quality of Life Outcomes from Botulinum Toxin Treatment in Spasticity: In a cohort of 50 patients, botulinum toxin treatment increased perceived quality of life and a decrease in maximum pain.

- Randomized Trial of Botulinum Toxin Type A in Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia — The SPASTOX Trial: In a sample size of 55 people, Botox treatments decreased muscle tone, but did not improve walking speed on a 10 meter walkway. Note that none of these individuals had SPG30, the spastic paraplegia present in KAND.

Literature on side effects and risk factors

- Systemic Weakness After Therapeutic Injections of Botulinum Toxin A: A Case Series and Review of the Literature: A review of the impact of Botox dose and frequency on side effects associated with muscle weakness.

Selective Dorsal Rhizotomy (SDR)

Rather than using chemicals to reduce activity in muscle reflex circuits, rhizotomy is the surgical removal of spinal cord nerves that receive signals from certain muscle groups. This permanently reduces circuit activity that contributes to spasticity.

Administration

SDR consists of removing a piece of bone from a spinal vertebrae and using X-ray and ultrasound to locate sensory nerves. The surgeon then uses electromyography to find specific nerves that contribute most to spasticity. These nerves are severed, and the surgical site is sewn shut.

Potential Benefits

By removing spastic nerves entirely, SDR is a one-time intervention that can reduce or eliminate the need for recurrent spasticity medications. By targeting specific nerves, SDR allows intact circuits to operate as normal. SDR has been shown to decrease spasticity and increase some quality of life measures.

Considerations

- Permanence: As a surgical intervention, SDR is irreversible.

- KAND-specific concerns: SDR is most often used in cerebral palsy, which has a stable pathology. It is crucial that SDR surgeons understand that KAND is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder in which intact spinal cord circuits may worsen over time.

- Recovery period: In the weeks or months following surgery, patients are likely to experience muscle weakness. Postoperative care includes daily physical rehabilitation in subsequent weeks, and therapy visits several times a week for several months.

- Dystonia: Some patients experience involuntary and painful muscle movements. By inhibiting spinal reflex circuits, SDR may unmask or worsen pre-existing dystonia.

- Long-term pain: Patients sometimes experience lower back pain years after SDR surgery.

- Spinal deformation: In some cases patients develop scoliosis, or spinal deformities. Because scoliosis also occurs in cerebral palsy (and KAND), it is still difficult to assess whether SDR is a direct risk factor for this symptom.

- Lower limb hypersensitivity: Some patients experience increased skin sensitivity in their feet and legs.

Literature on use and benefits

- Selective Dorsal Rhizotomy for Treatment of Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia-Associated Spasticity in 37 Patients: A study of SDR in hereditary spastic paraplegia patients, including one SPG30 KAND patient, with long-term improvement in the majority of patients with some side effects.

- Surgical treatment of spasticity in children: comparison of selective dorsal rhizotomy and intrathecal baclofen pump implantation: A study assessing patient outcomes for SDR and intrathecal baclofen found both to be effective, with SDR having a bigger impact on muscle tone.

- Selective dorsal rhizotomy for spasticity not associated with cerebral palsy: reconsideration of surgical inclusion criteria: A review of SDR for broader neurological disorders found that most patients’ leg spasticity improved, though neurodegenerative progression still continued.

Literature on side effects and risk factors

- Risk factors for progressive neuromuscular scoliosis requiring posterior spinal fusion after selective dorsal rhizotomy: A retrospective study of pediatric patients undergoing SDR. Preoperative side-to-side spinal curvature and inability to walk are potential risk factors for further spinal deformities following SDR.

- Selective dorsal rhizotomy for spasticity of genetic etiology: A review of SDR for genetic spasticities found that while SDR consistently improves spasticity, its long-term effects on gross motor function varied.

Dr. Jennifer Bain and Dr. Jackie Montes on Spasticity in KAND

At the 2022 KAND Family & Scientific Engagement Conference, Dr. Jennifer Bain and Dr. Jackie Montes of Columbia University discussed spasticity and KAND, including potential treatment options. You can access the presentation slides here.