One challenge in improving quality of life for patients and loved ones affected by KIF1A Associated Neurological Disorder (KAND) is that there are not always clear-cut answers for symptom management. While we don’t have all the answers, we’ve gathered some resources on epilepsy in KAND that you can discuss with your doctor when making decisions about care.

Your brain is a well-regulated lightning storm; at any given moment electrical signals are flowing through billions of neurons that help you see, feel, move, talk, and even breathe. Much like the electrical wiring to your house, you can harness that electricity effectively and “do it all” because it’s routed through the right cords to the right appliances.

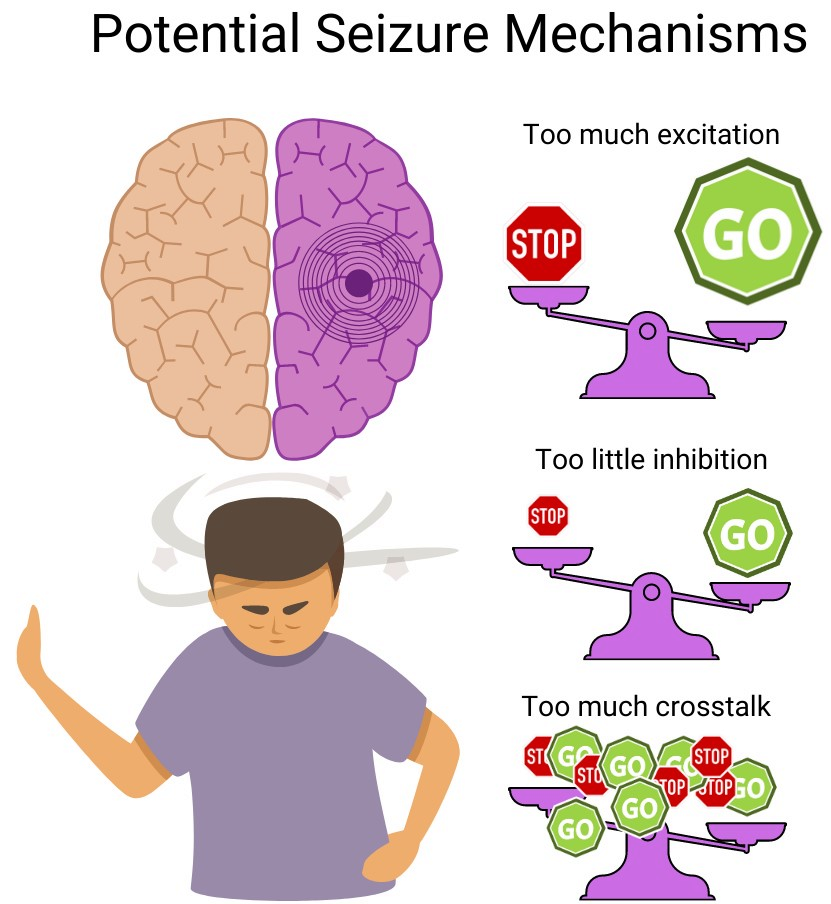

You can imagine a number of ways this situation could go wrong:

- The outlet voltage is too much for the appliance (neurons are too excitable)

- Short circuits (abnormal functional or anatomical wiring)

- A live wire (electrical irritability)

When a change in the brain’s electrical state causes a change in behavior, we call that event a seizure. Anyone can experience a seizure, but under normal circumstances the brain’s safety mechanisms prevent them. People who are disposed to experiencing repeating, stereotyped seizures are considered to have an epileptic disorder.

Identifying epilepsy

Because epilepsy is defined by seizures that can be subtle, short-lived, variable in appearance, and stressful for everyone involved, it can be difficult to diagnose.

To envision this more intuitively, imagine your brain as a pond. The pond is constantly experiencing ripples in response to animals and wind and dropping objects; those ripples will bump into one another and interact as part of a larger pattern. A seizure is like a crashing wave that overtakes all of those smaller ripples.

If this big wave happened once, it might be hard to figure out why it happened. But if the big waves keep disrupting the quiet peace of the pond in the same way, we might look for patterns and causes: Maybe somebody practices their cannon-balls in the pond or skips rocks, or maybe there’s something underneath the water. Epilepsy is an umbrella phrase for things in the pond that might cause disruptive waves.

This is further complicated by the fact that definitions of epilepsy and seizures have shifted over time as our understanding of the brain advances. A good place to start is with how the seizures impact the patient

Seizure types

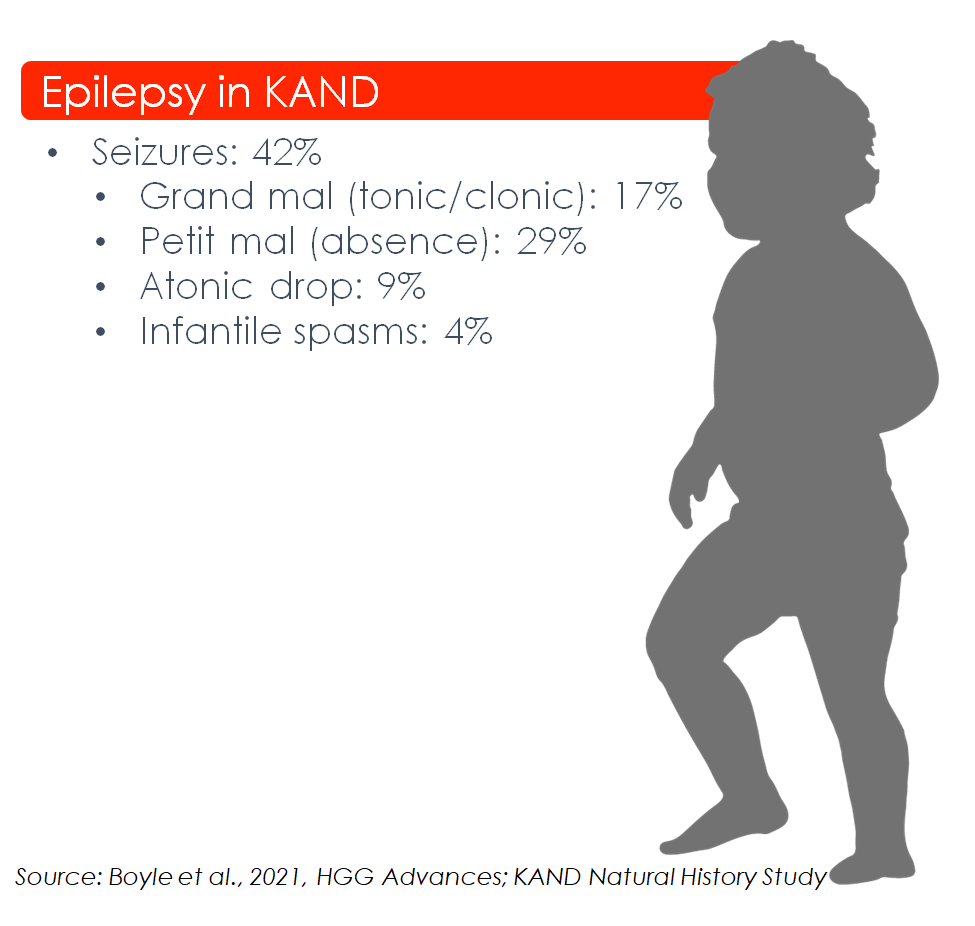

These are the endpoint “effects” or “symptoms” of the seizures, and the first sign that is likely to alert families about potential epilepsy. Different patients have different seizure types, and one patient may experience multiple types; here is a list of seizure manifestations seen in KAND:

- Absence: Staring into space while nonresponsive, may repeat small movements.

- Tonic: Involuntary stiffening of muscles.

- Clonic: Involuntary jerking of muscles.

- Atonic: Involuntary relaxing of muscles, can cause falls.

- Infantile Spasms: These are subtle changes to movement or behavior in infants; split-second spasms, jerking nod-like movements, and sudden curling of the legs while laying down. In some cases these can accelerate progression of other developmental or degenerative symptoms. Because the brain’s electrical network is developing during this period, early diagnosis can be crucial for effective treatment.

- Developmental/Epileptic Encephalopathy with Spike Wave Activation in Sleep (DEE-SWAS), also known as Continuous Slow Spikes and Waves during Sleep (CSWS): Some KAND patients have more abnormal electrical activity when they sleep than when they’re awake. Slow waves and spikes aren’t necessarily seizures, but their abnormal activity can disrupt a child’s sleep as well as their cognitive development and attention.

Patients without epilepsy may experience similar-looking symptoms; working with a clinical specialist is crucial for distinguishing epilepsy from other neurological disorders.

Visiting your Epileptologist

Epileptologists are clinicians who specialize in interpreting the brain’s electrical activity during the diagnosis and treatment of epilepsies. We’ve consulted with Dr. Tristan Sands, co-lead of the KAND EEG study, to create a one-page resource on epilepsy in KAND to guide your initial conversations:

What information should I provide about KAND?

- KAND is a progressive developmental and neurodegenerative disorder

- Approximately 50% of KAND patients have reported seizures and many others have abnormal EEGs without obvious seizure activity

- Half of epileptic KAND patients had their first seizure before age 10

- Epilepsy types vary between KAND patients

- Developmental/Epileptic Encephalopathy with Spike Wave Activation in Sleep (DEE-SWAS) also known as Continuous Slow Spikes and Waves during Sleep (CSWS), is commonly observed in KAND

- Seizures in KAND can be followed by cognitive decline

What should I ask for?

Overnight/24hr EEG: Dr Tristan Sands from Columbia University Medical Center co-leads the KAND Epilepsy and EEG study. Because KAND can cause abnormal electrical activity during sleep, he and other KAND specialists highly recommended an EEG with recorded sleep, or ideally an overnight/24hr EEG. These longer recordings are more likely to detect abnormal activity, including epileptic spikes and seizures at night.

There are two primary factors that contribute to epilepsy diagnosis:

1. Observations of patients during seizures

What should I bring to my appointment?

Video recordings of suspected seizures are one of the best tools families can provide their epileptologist; seizures are stressful events and self-report/interviews may miss crucial details. Seeing which aspects of a patient’s behavior change can inform clinicians about what might be happening in the brain.

2. Measurements of the brain’s electrical activity with an electroencephalogram (EEG)

EEG

There are many types of seizure, even when we know the primary cause is genetic in KAND. Seeing the “source” of the seizure with EEG is crucial for understanding the type of seizure and impacts the management and treatment. For example, EEG can determine where in the brain the seizures originate:

- Focal: These seizures begin with inappropriate activity in one brain region, which then spreads to others.

- Generalized: These seizures begin as excess activity across the brain.

This information is crucial because the area in which seizures originate can be related to the types of seizure symptoms the patient experiences.

EEG also lets epileptologists look for nuances that can help distinguish seizure types, or even identify abnormal electrical activity that happens between seizures; these all play a crucial role in diagnosing and treating epilepsies.

After your visit

Request Raw files for KAND EEG study: Once your EEG is complete, you can request that your physician provide a raw EEG data file afterward. Our clinical researchers need these data files for the first-ever KAND-specific EEG study to find patterns within our community.

Considerations for medications

For a disease community as heterogeneous as KAND, it’s important to consider how different symptoms can be researched and therapeutically approached. There are many advantages to investigating epilepsy in KAND:

- Anti-epileptic drugs may cause allergic reactions in children and unexplained rashes, fevers, and other symptoms emerging during initiation of treatment should be reported to the physician.

- Ideal anti-epileptic drugs have their effect as brain activity ramps toward a seizure, with less effect during normal activity, meaning that in the ideal scenario benefit is maximal and other effects on brain function are minimal.

- Some side effects like sedation may improve with time, but the overall benefits and costs of each medication must be weighed when deciding to switch or continue.