You asked so many great questions at our 2022 KAND Family & Scientific Engagement Conference. While we didn’t have time to address every question at the conference, we’ve compiled our answers here for your convenience.

You can find all of the presentation recordings and slides on our 2022 KAND Conference webpage. Do you still have a question? Contact KIF1A.ORG Research Engagement Director, Dr. Dylan Verden, at dylan@kif1a.org.

Q. What are common KAND symptoms?

A. KIF1A Associated Neurological Disorder has a wide range of symptoms and severity. No two patients are affected the same way. According to the Chung Lab/Columbia University Natural History Study of KAND patients (as of August 2022 with 142 patients), the most common symptoms are developmental delay/intellectual disability, overall vision/eye conditions, hypotonia, hypertonia, abnormal MRI, cerebellar atrophy, optic nerve atrophy, and seizures. Some of these symptoms are likely underreported due to poor diagnosis and complexity of symptoms. View this clinical snapshot and more information from the Chung Lab KAND Study Update at the 2022 KAND Conference here.

Q. If you are heterozygous for your KIF1A mutation, does it mean you make 1 healthy protein for every “broken” protein? Do the “broken” ones cause a traffic jam that healthy proteins have to wait for?

A. This is accurate for most mutations: While the ratio may vary, people who are heterozygous* for a KIF1A mutation make both broken and healthy KIF1A.

*Heterozygous means “different.” Most people have two copies of the KIF1A gene (some people are known to have deletions or duplications). People with a heterozygous mutation have 1 healthy copy and 1 broken copy.

Because KIF1A works in pairs called dimers, healthy and mutant KIF1A interact directly in heterozygous individuals. Mutant-mutant pairs may cause traffic jams for healthy-healthy pairs. Healthy-mutant KIF1A dimers will also have different movement patterns that impact cargo transport. For more information on heterozygous dimers, check out this #ScienceSaturday blog post, our Research Roundtable summary from Dr. Shinsuke Niwa, and the Ovid Therapeutics 2022 KAND Conference presentation from Dr. Noelle Germain.

Q. If there is a particular protein that is deficient, can we not find a way of increasing the protein?

A. One challenge in treating KAND is that for many patients, it isn’t simply that there isn’t enough KIF1A. Most mutations in KIF1A create a version that doesn’t function properly, and interferes with cargo transport by healthy KIF1A. The effects of overexpressing healthy KIF1A aren’t entirely known, but ideally we would want to reduce the amount of mutant KIF1A so that healthy KIF1A can do its job.

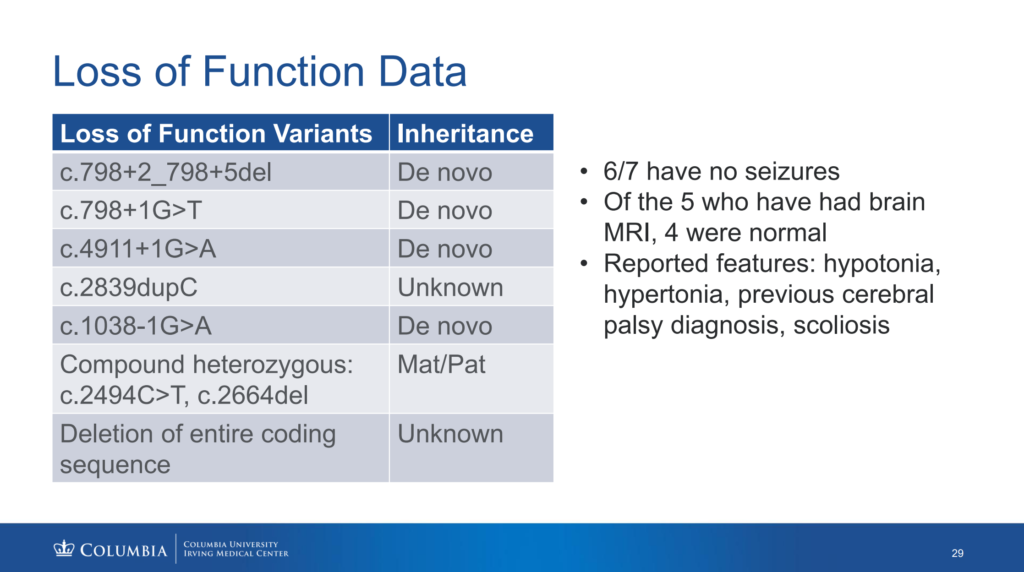

Q. What are loss-of-function mutations, and how are they different from other KAND variants?

A. First, let’s remember that healthy people have two copies of the KIF1A gene, and each KIF1A gene creates instructions for bodies to produce healthy KIF1A protein. Most people with KAND have one mutated copy of the KIF1A gene and one healthy copy of the KIF1A gene. Gene mutations can be classified as “loss-of-function” or “gain-of-function.” Gain-of-function mutations lead to a new molecular function or expression of the protein, while loss-of-function mutations lose function of the protein compared to the healthy version. The 1038-1G>A mutation, discussed during Dr. Wendy Chung’s presentation, is an example of a loss-of-function mutation. While many mutations create a full KIF1A protein that misbehaves in a way that interferes with healthy KIF1A, certain loss-of-function mutations fail to create a full KIF1A. So, these loss-of-function KIF1A proteins don’t really function at all. People with these mutations still produce healthy KIF1A proteins from their healthy copy of the KIF1A gene, but they produce fewer healthy KIF1A proteins than healthy people. Still, some clinical reports from people with loss-of-function mutations show milder symptoms compared to patients with gain-of-function mutations. For example, patients with loss-of-function mutations report fewer cases of seizures. This is important when considering treatment development.

- Some of our therapeutic strategies focus on knocking out mutant KIF1A. This would result in a single copy of healthy KIF1A, making other variants more similar to loss-of-function variants (potentially a milder form of KAND).

- Because people with loss-of-function variants still do not produce the same levels of KIF1A as healthy people, treatments that increase KIF1A levels could potentially be explored as a therapeutic option.

Q. Is it possible to 1) knock down the mutant copy of KIF1A, and 2) overexpress the healthy copy of KIF1A?

A. This would be an ideal treatment scenario, but each step needs to be validated independently as well as in combination. Our partners at Ovid Therapeutics are currently researching mutant-specific knockdown of KIF1A, and the effect of these knockdowns will inform whether overexpression of healthy KIF1A would also be helpful. For example, the body could naturally overexpress the healthy KIF1A after the mutant copy is knocked down.

Gene therapies that replace mutant KIF1A sequences with healthy ones would likely not require overexpression of KIF1A since the patient would have two copies of the healthy gene.

Q. I’ve been diagnosed with a variant of unknown significance in my 50s. Why would it only show up now?

A. Genetic sequencing is still an advancing field, and we are more equipped to find mutations than we were even a decade ago. It is likely that this mutation has always been present, but there isn’t sufficient data to determine whether this mutation is pathologic. Some mutations may not impact KIF1A function. Both genotype and symptoms should be considered together when determining whether someone with a KIF1A mutation has KIF1A Associated Neurological Disorder. We encourage people with KAND symptoms and a known KIF1A mutation to contact the Chung Lab by emailing kif1a_study@cumc.columbia.edu for more information.

Q. At what point in our medical diagnosis journey, post genetic test results, do you wish that we contact the natural history study?

A. If you or a loved one received a genetic report with a KIF1A mutation, we encourage you to email genetic researchers at Chung Lab with Columbia University at kif1a_study@cumc.columbia.edu. Chung Lab is compiling a worldwide registry of people with KIF1A mutations, including those with a “variant of uncertain significance.” If you have a “pathogenic” or “likely pathogenic” KIF1A mutation, you may be eligible for the KIF1A Natural History Study, which includes medical history interviews and questionnaires that can be completed over the phone or online to help researchers better understand KIF1A Associated Neurological Disorder. Learn more here. Eligible patients may also participate in the KOALA Study, an in-person research study at Columbia University in New York City. Learn more here.

Q. Have any studies correlated seizure activity or cerebral atrophy and cortical visual impairment? Is there a reason to expect that cortical visual impairment is under-identified as in CDKL5 & Rett?

A. Cortical visual impairment is a known symptom among some KAND patients and likely associated with cerebral atrophy that can worsen with seizures. Cortical visual impairment is likely under-identified because not all KAND patients have received MRIs. 83% of KAND patients have some form of visual impairment, but the causes may vary – 43% have optic nerve atrophy, while 16% have identified cortical visual impairment.

Q. If medication is effectively controlling seizures, would you recommend discontinuing medication if no seizures have occurred in years?

A. Some patients with epilepsy can stop taking medication after two years without seizures, but because seizure type and severity vary across the KAND community there are no KAND-specific guidelines. Discontinuation of seizure medications should be discussed with your physician and closely monitored for any return of symptoms.

Q. Where does sensory motor under-responsiveness come into KAND?

A. Our sensorimotor circuits are comprised of many different senses that can be impacted by KIF1A mutations differently. While spasticity is related to hyperresponsive reflexes to movement and muscle stretching, many KAND patients have high pain tolerance and altered temperature sensation. We’re still learning why KAND makes some circuits over-responsive and others under-responsive.

Q. Can we have a list of medications that we know can help with visual problems, brain development, etc?

A. We do not currently have a comprehensive list of effective medications for all symptoms of KAND. This is partly due to the complexity of some of these symptoms, and partly because KAND treatments have largely been applied on a case-by-case basis by individual physicians. One resource we plan to develop are a set of patient care guidelines for clinicians that provide more standardized approaches to treating different components of KAND. However, we have compiled some resources on specific symptoms:

- For information on seizure and spasticity medications used in our community, you can find the results of our 2020 Seizure and Baclofen Survey at our Private Family Resource Page.

- You can find a discussion of spasticity management, including treatment options, at our KAND and Spasticity Page.

- You can find more information about treatments reported being used by families in Dr. Wendy Chung’s 2022 KAND Conference presentation.

Q. What end-points are you going to study in KOALA? Given KIF1A has such a broad phenotypic spectrum? Should you maybe subgroup KIF1A individuals into those with common phenotypes?

A. The KOALA study will assess a wide variety of domains that affect quality of life in the KAND community, including spasticity and walking, vision, and epilepsy.

The most important part of the KOALA Study is getting as many KAND families to participate as possible. Once Columbia University researchers have analyzed this data, it can be assessed with different subgroups in mind, reflecting both genotypic and phenotypic variability. This will help us create better-informed endpoints, which may be tailored for different subgroups in the KAND community.

Q. Some KIF1A variants are non-hotspot. Any ideas to develop a functional assay that can classify all new KIF1A pathogenic variants? To provide insight in prognosis/extent of disease? Maybe using CRISPR-CAS?

A. One challenge in understanding KIF1A mutations is that the protein structure hasn’t been entirely resolved yet. This means that outside of the motor region, it can be difficult to know how a new mutation will impact KIF1A function. Our Research Network is working hard to better understand healthy KIF1A structure so that we can better predict the effects of mutations on KIF1A function. Creating cell lines with disease-associated mutations in different regions of KIF1A is also crucial to understanding variants: we currently have 6 patient-derived cell lines and 10 genetically engineered cell lines carrying disease-relevant mutations, and our partners at NeuCyte and BioLoomics are creating assays that we intend to scale up to assess multiple mutations. However, we don’t currently have a high throughput assay that can classify all KIF1A variants in parallel.

Q. Can experiments in patient-derived neurons and organoids be used to test not just drugs, but also treatments like gene therapies?

A. Absolutely! Once differences between healthy and KIF1A-mutant cells and organoids have been defined, we can test both traditional medications and gene therapies to look for a restoration of function. It’s important that our tests be useful for testing our parallel efforts.

Q. How are drugs identified as potential meds for KIF1A? If some drugs are promising in the initial screen, how do you pick which to invest time and experiments in?

A. Because KAND is an umbrella for many symptoms, we often look to medications that alleviate these symptoms in other disorders. Testing these medications in model systems, such as patient-derived neurons, organoids, and mice, gives us more information on whether these are worth pursuing in KAND.

One reason we and our partners have invested in medium- and high-throughput screening is because we want to test many treatments in parallel. When deciding how to invest in promising treatments there are multiple considerations:

- How robust was the effect of the drug on disease-relevant symptoms?

- Did the drug have any negative effects in our assays?

- Does the drug have a known safety profile?

- If the drug is not already on the market, has it been used in clinical trials?

- How would a drug need to be administered to treat people?

Q. Is it possible for genetic treatments to not just stop the progression of symptoms, but also improve them?

A. To answer this question it is important to understand that two major factors contribute to KAND symptoms: Effects caused by current KIF1A dysfunction, and cumulative effects from past KIF1A dysfunction.

Genetic treatments are the most direct way of treating KAND, because they change the relative expression of mutant and healthy KIF1A. This will likely stop the progression of some symptoms and improve some over time. However, some symptoms initially caused by KIF1A dysfunction may persist after genetic treatment. It is likely that the effects will vary by individual and when they received the treatment. Until we get to clinical trials it is difficult to predict which aspects of KAND will improve.

In the “Clinical Snapshot of Symptoms and Features” (Boyle et al) those data were collected, in some cases, over four years ago. In that time the KAND population of identified patients has grown exponentially — more than doubled. We’re working on an updated version, which I think will have significantly higher percentages of individuals with characteristics listed above; particularly seizures, reflux, and cortical vision impairment. We’re working on tools like community surveys and more data from the KOALA Study (https://www.kif1a.org/the-koala-study/) that will give us a more current idea of disease characteristics and the percentage of individuals affected by those symptomatic characteristics of KAND..