#ScienceSaturday posts share exciting scientific developments and educational resources with the KAND community. Each week, Dr. Dominique Lessard and Dr. Dylan Verden of KIF1A.ORG summarize newly published KIF1A-related research and highlight progress in rare disease research and therapeutic development.

Murdoch Children’s Senior Researcher Simranpreet Kaur received the 2022 MDHS Award for Excellence in Engagement from University of Melbourne

One of the defining features of KIF1A.ORG is an engaged Research Network, full of scientists who ground their projects in patient perspectives and priorities. This is why we are so excited to congratulate Dr. Simranpreet Kaur (Sim for short) at the University of Melbourne for receiving an MDHS Award for Excellence in Engagement!

Dr. Kaur is an integral member of our Research Network whose transparency and collaboration underlie her success. In 2020 KIF1A.ORG was proud to provide pilot funding for her work to develop high throughput drug screens for KAND, and in 2021 she was awarded a $775,019 AUD grant from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council to study epilepsy treatment for KAND.

“I am obliged to have received this award which honours my existing partnership with KIF1A.org, a patient-led research organisation dedicated to accelerating research to find treatments for KIF1A-Associated Neurological Disorders (KAND), an ultra-rare childhood onset neurodegenerative disorder. Integrating consumers perspectives into research is critical and this award will further support my compassionate engagement with local and international groups.”

Dr. Kaur

Congratulations Sim, and thank you for all that you do for the KIF1A community!

KIF1A-Related Research

Expanding the Knowledge of KIF1A-Dependent Disorders to a Group of Polish Patients

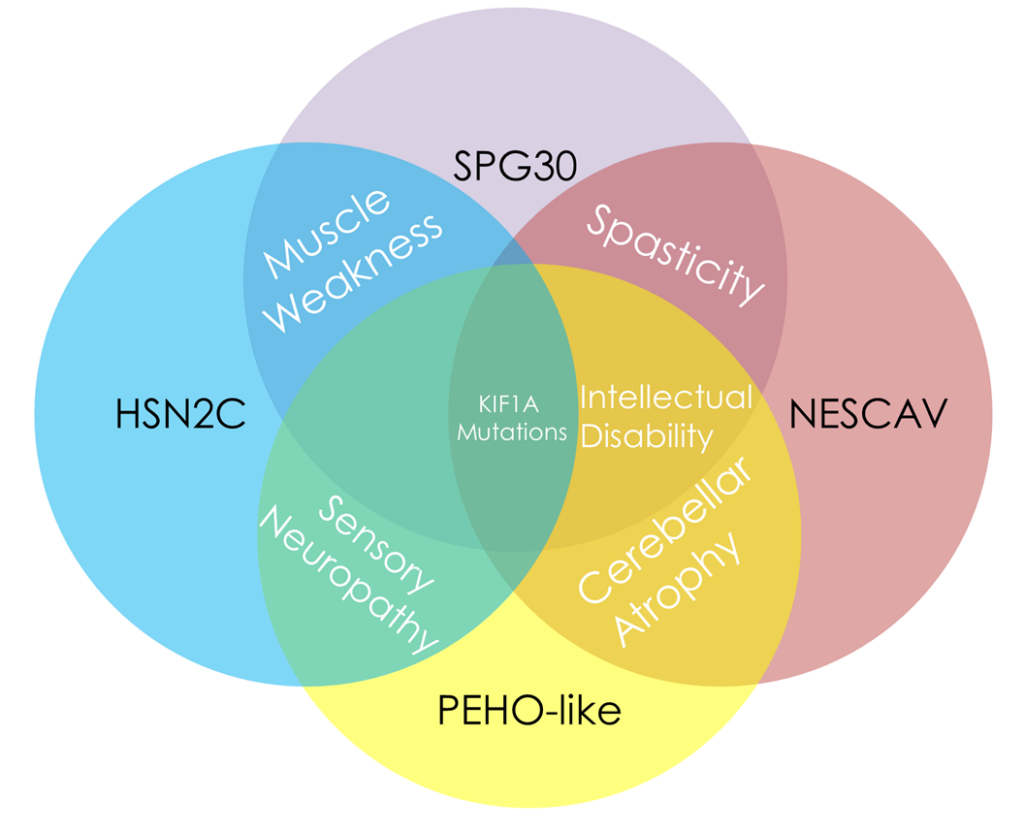

- Spastic Paraplegia Type 30 (SPG30)

- Hereditary Sensory and Autonomic Neuropathy Type 2 (HSN2C)

- Neurodegeneration and Spasticity with or without Cerebellar Atrophy or Cortical Visual Impairment (NESCAV)

- Progressive Encephalopathy with Edema, Hypsarrhythmia, Optic Atrophy (PEHO)-Like Syndrome.

Other than being a mouthful, what do the above disorders have in common? They’re all clinical diagnoses received within the KIF1A family community.

But isn’t the disease caused by KIF1A mutations called KAND? Are these other disorders examples of misdiagnosis? Well, not exactly.

We’ve talked in past posts about the difference between a genetic diagnosis and a symptom-based diagnosis, and how KAND is a disease at the intersection of KIF1A mutations and a wide variety of clinical symptoms.

For example, without a genetic test KAND can look very similar to cerebral palsy. The reason we call this a misdiagnosis is that unlike cerebral palsy, diseases caused by KIF1A mutations are neurodegenerative – this is key when considering disease management and treatment.

SPG30, NESCAV, HSN2C, and PEHO-Like Syndrome are also symptom-based diagnoses, but they accurately describe many factors of KIF1A-related disease. In a patient with KIF1A mutations and spasticity, but few other symptoms, we might call the disorder “KIF1A Associated Neurological Disorder manifesting as simple SPG30,” or “KAND with simple SPG30” for short.

Because KIF1A mutations can cause such a wide variety of symptoms, it makes sense to have an umbrella of symptom-defined disorders; treatment approach should be informed by symptoms. But these labels can also make it difficult to draw a clinical profile of KAND, which can manifest very differently between patients, even those who carry similar mutations.

In this week’s article, clinicians and researchers in Poland reported on 9 patients with KIF1A mutations causing a wide variety of symptoms. The authors noted that “We had difficulty classifying them among individual phenotypes due to overlapped clinical pictures and dynamically changing phenotypes.” In other words, the complicated nature of KAND made it difficult to place patients in these symptom-defined buckets.

We know that KAND can vary by mutation type – for example, mutations outside KIF1A’s motor domain are more likely to be inherited and cause sensory symptoms observed in HSN2C. So the authors compared their patients to others with the same mutation, reported in the scientific literature. While they found overlap between patients with the same mutation, there were also considerable differences.

This is important. When clinicians are diagnosing patients the first thing they look at are the symptoms; if KIF1A mutations are most commonly known for spasticity, a doctor might not look for KIF1A mutations in a patient experiencing progressive weakness, which could be a reason for underdiagnosis of KAND.

The authors make another very important point – diseases change over time. A patient with features of NESCAV at one age may experience more spasticity over time and start to look more like SPG30. With this kind of variability in disease, data from more people, and data over time, play a huge role in our understanding of KAND. This is the reason our survey-based Natural History and in-person KOALA studies are so important to inform our clinicians, and our therapeutic pipeline.

Rare Roundup

CBER to Launch Operation Warp Speed for Rare Diseases by Year’s End

Medical research and development move slower than we want them to. While regulation is necessary to ensure the effectiveness and safety of new therapeutics, this process can be cumbersome, especially for rare disease communities with limited resources.

But during the COVID-19 pandemic, we saw this process streamlined as companies developed new vaccines in record time. Operation Warp Speed reflected the urgency of the pandemic, and led to accelerated approval and use of vaccines.

While rare disease patients are fewer in numbers, their need is no less urgent. In an effort to learn best practices from the COVID-19 pandemic, the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) is planning to implement an Operation Warp Speed for rare diseases by the end of 2023.

The goal is to accelerate the introduction of rare disease therapies to the market while maintaining safety regulations. This includes broadening the scope of clinical endpoints that can be used during the approval process, as well as maintaining more regular communication between developers and regulators. Increased communication could be a huge benefit by allowing developers to receive feedback as they conduct studies and trials with their therapeutic candidates.

This is only the beginning of the process to make a more effective regulatory pipeline for potential treatments, but a sign that the FDA is working to address the urgency of rare disease communities.