While I think most of our readers will understand the enormity of today’s title, it’s worth stating explicitly that Susannah Rosen is on a huge journey.

We often call members of our community Superheroes, but internally I default to another term Luke Rosen and advocates use often: Pioneers. In fact the Yellow Brick Road Project, representing patients with HNRNPH2 mutations, dubbed this the Year of the Pioneer, a banner we’re happy to spread: It reflects the unknown course of navigating a disorder and its treatments, the vulnerability, and the bravery required to risk dangerous lands for a chance at safer havens.

Thanks to relentless work by the Rosens, Wendy Chung, Jennifer Bain, and the incredible teams at n-lorem and Columbia University, we now have a logbook of that journey’s first year.

And with apologies, this summary won’t be very short: The study was concise, but there’s a lot of context to appreciate where Susannah is, and what it means for our community. She’s done the heavy lifting, so join me for a long walk.

What this study is – and isn’t

Through recent years, ASOs have been a major point of discussion in our community. We’ve been able to discuss the guiding philosophy and design, the steps of research, and more recently the potential amenability in our wider community. But at the core of it all, spoken or unspoken, there has been a looming question:

“How’s Susannah?”

And while the Rosens have been open books when asked about their experiences, we’ve also always cautioned that the study is still underway. When we hit these kinds of milestones after all that buildup there’s a sense of – or hope for – catharsis; these are the answers we’ve been waiting for, after all.

I think these times of excitement are when it’s important to take great care.

This study is not a definitive answer; it’s a snapshot, the first 300 days of a journey that Susannah is still pioneering today. For her the date of publication was another day in the wilderness, roughly a week after her last dose, and a couple months before the next. She is still a developing child, and we don’t know exactly how the ASO will interact with future milestones.

This study is also not comprehensive; as the first KAND ASO pioneer, Susannah’s experiences – expected and especially unexpected – have informed the study team to improve the quality of future observations and assessments.

But this snapshot is invaluable, because it shows that one child has been helped – not cured, but given a little more of herself back. And if the pioneer got there, others can follow.

This study gives us clues on what to look or hope for, and where we can fill the gaps with other therapeutic shots on goal. It’s the result of thousands of hours of work by dedicated people, spanning from advocates to basic research to clinical teams. As we review the data below, I cannot overstate how exciting it is to see published evidence that Susannah’s journey has been worthwhile.

Susannah’s ASO Treatment Regimen

A brief note: Throughout this post I will be citing the original article; unless otherwise noted, quotes are sourced from Ziegler et al. 2024. To maintain the original study language and prioritize an accessible format, numbers and statistics relating to specific tests have been removed from study quotes. The use of ellipses (…) represents skipped text that can be referenced in the original report. The use of brackets ([]) indicates personal clarifications.

Susannah is being treated with an Antisense Oligonucleotide (ASO): To break down the term, this is a molecule designed with a sequence of 20 (oligo, “few”) letters of DNA (nucleotide) that match a sequence on the mutant KIF1A RNA (Antisense) and knock it down. This allows Susannah’s healthy copy of KIF1A to do its job unhindered.

This ASO was injected into the spinal cord, starting with a low dose that increased over time. As you can see, the interval between doses also increased from an initial 1 month to roughly 3:

- Start, 20mg

- Day 30, 20mg

- Day 58, 40mg

- Day 115, 60mg

- Day 207, 60mg

- Day 301, 80mg

These doses are still being optimized so patients that follow have the safest, most effective schedule possible.

What Symptoms were impacted?

Cognition

Cognition can be a charged term, in part because it can represent so much. In research we rely on operational definitions – highly specific, limited definitions that allow us to make testable hypotheses. But when those terms get used again in broader settings, things can get lost in translation. Here’s an example:

Her cognitive performance was generally stable… with low end of average verbal abilities, low nonverbal abilities, and very low spatial abilities. Her memory performance was also low across time points. Her overall intellectual composite was stable.

Without context this could be framed as “her cognition didn’t improve”, or “her cognition didn’t get worse.” So let’s add some context:

In this statement, “cognitive performance” is shorthand for “performance on the Differential Ability Scales measurement,” a specific assessment that measures cognitive functions like pattern recognition and verbal reasoning.

That isn’t to say there weren’t improvements: There is more to the story when we look at traits that we, in our day-to-day lives, associate with cognitive ability:

There was improvement in quality of speech, with longer sentences, less dysarthric speech and improved prosody and intonation. Her level of attention was improved, with faster response time to tasks and improved ability to follow multistep commands.

These are the kinds of changes that can mean everything for quality of life. To paraphrase two inspiring rare disease parents and advocates speaking about their children:

“She still can’t do math, but improved speech, better attention – to us these are cognitive improvements.”

Luke Rosen, personal communication

“I want to know if somebody hurt her while I wasn’t there, and I want to hear the highlight of her day.”

Kim Nye, SLC13A5 Research Conference & TESS Family Day,

Movement

Movement is a single word describing an incredibly complex collection of abilities, so it’s worth pulling out some of the nuance. One of the primary endpoints of this study was performance on the 6-minute Walk Test.

Spasticity persisted in both lower extremities with progressive scissoring. There was minimal change in the distance walked during the 6-min Walk Test.

Just like cognition, this seems pretty grim without context; spasticity is a movement feature we talk about often in KAND, after all. But let’s step back from spasticity as a symptom and toward functional behavior:

The motor exam showed improvement in pulling to stand, initially needing assistance and later able to stand up from sitting on the floor… There were improvements in hand tremor amplitude, dysmetria on finger-to-nose testing and ataxia when walking…

Improvement in gait was noted in the month after the first dose, and the number of falls decreased to a maximum of seven per day, with many days without falls despite an increase in overall activity and ambulation…

The Gross Motor Function Measure-66 score also showed mild improvement over the assessment period.

Together, this picture provides two takeaways: 1) Spasticity as a symptom may require earlier ASO intervention or a different treatment, and 2) The 6-minute Walk Test might not be the best reflection of meaningful changes to functional movement.

This is another area where aligning clinical measurements with family priorities will be crucial moving forward:

One of the biggest differences to us has been the reduction of tremors, because Susannah’s improved ability to feed herself frees up precious seconds for Sally and I.

Luke Rosen, personal communication

Epilepsy

Epilepsy is one of the most complicated symptoms we deal with – not only because of its complex presentation in KAND patients, but also the fact that definitions in epilepsy research are still being refined.

Identifying a seizure or epilepsy subtype relies on both behavioral observations, and readouts of electrical activity by EEG. Susannah’s sudden absent spells, reported by the Rosens as seizures, weren’t accompanied by specific seizure-related activity on the EEG, despite epilepsy-related activity between events.

Because of this disconnect, these events are described as “spells of behavioral arrest” in the study. Since this term might not be familiar to families in our community, these are staring or absent spells that we typically log as absence seizures.

At run-in (the 50 days before the first dose), surveys completed by the parents reported between 100 and 290 spells of behavioral arrest per day in the 4 months before the first dose… The daily number of spells of behavioral arrest reported by the parents dropped after the first dose and was less than 30 in the week after the most recent dose of 80 mg. In addition to lower spells of behavioral arrest frequency, the longest was considerably shorter…

After initiating the ASO, the EEG demonstrated improvements with greater organization after the second dose that persisted, with a reduction in the frequency of epileptiform spikes [as measured by reduced Spike Wave Index during overnight EEG].

So even though the exact relationship between these seizure-like events and their EEG correlate aren’t entirely understood, it is encouraging that both improve in response to ASO treatment.

Luke and I also discussed that this ASO wasn’t introduced in a vacuum; Susannah has also been on anti-seizure medications that were adjusted over the course of the study, and these interactions will be important to consider for children with broad symptoms and multiple medications.

What unmet needs remain?

We have always tried to be clear that no treatment is a silver bullet, which is one reason we maintain multiple shots on goal. These are areas where Susannah is still experiencing unmet needs.

Vision

Because this ASO is administered through the spinal cord, it does not have access to the cells of the eye and optic nerve, and we did not anticipate any benefits for Susannah’s vision. The effects of an ASO administered to the eye have yet to be determined, and we are also investigating small-molecule therapies to treat this high-priority symptom.

Gastroesophageal Reflux

This is a symptom that sits where vision did last year – high impact and understudied. Reflux impacted 34% of KAND participants in the online Natural History Study. Similarly to the eye and optic nerve, the ASO may have limited access to these tissues.

Spasticity and difficulty stepping

While many elements of movement improved, Susannah’s spasticity remained an issue, and leg scissoring limited her movement. The neurons from our spinal cord and legs have the longest axons in the human body, and may have been particularly vulnerable to the loss of long-range KIF1A transport. Regardless of mechanism, improving mobility by reliving spasticity is still an important therapeutic target.

Peripheral neuropathy

Susannah continued to experience neuropathic pain in her feet, and this may also be a consequence of the long neurons of the lower limbs. Pain is a difficult symptom for patients who struggle with communication. KAND families have reported both reduced sensitivity to injuries and burns, and the presence of pain or tingling in extremities, which is important to consider when considering therapies.

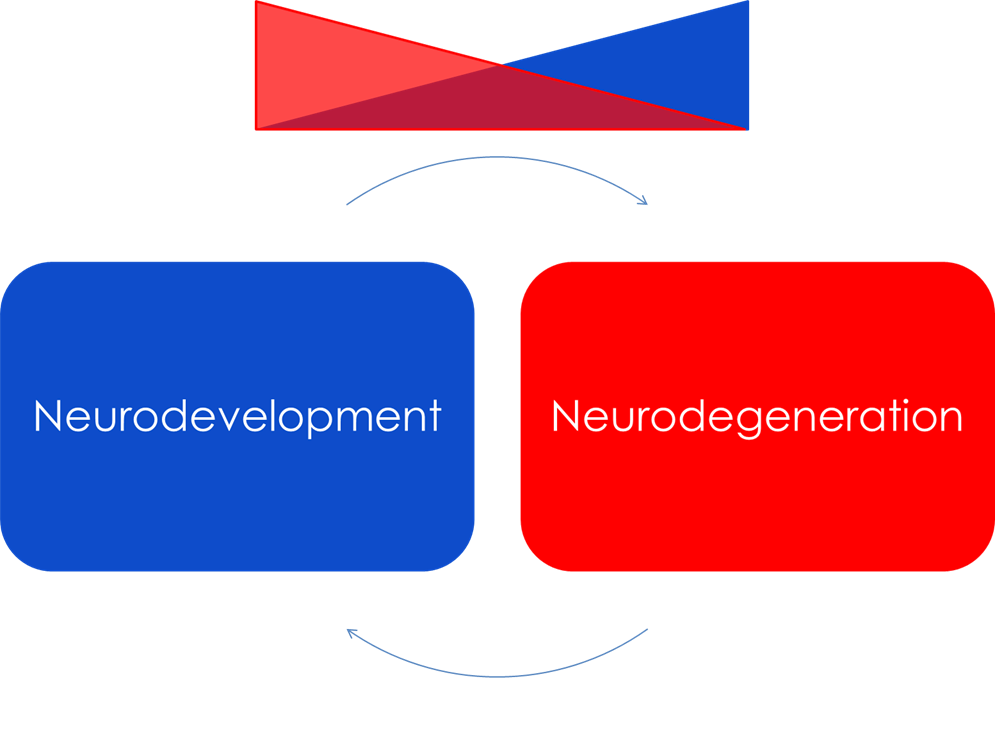

Will this __________ KAND? Neurodevelopment, neurodegeneration, and treatment

During my PhD I studied the impact of ischemic stroke in the juvenile vs the adult brain, which taught me about the complex intersection of neurodevelopment and neurodegeneration.

The language of developmental delay carries a bit of dishonest imagery; the brain doesn’t biologically stop developing or stall out, waiting for the right treatment to start it up again on its intended path.

The processes that underlie our own development – physical growth, metabolic changes, and circuit refinement to name a few – are still happening in KAND, just along a dysfunctional trajectory. These are periods of vulnerability to cellular injuries, like those caused by mutant KIF1A and mislocalized cargo. As these events snowball into circuit-level dysfunction, the situation becomes more complex.

The recent Natural History Study highlighted that functional decline is more pronounced in patients who were observed at younger ages, and this may reflect critical windows for KIF1A biology. The chance of reversing or relieving certain symptoms may be a matter of timing – when did mutant KIF1A push this patient’s snowball down the hill, and how early can we intervene?

I don’t think I’ve heard anything more difficult in these conversations than Luke’s fear that “the treatment works, but KAND might be outrunning it.” Or rather, its head start was too great. Susannah is 9 years old: her brain is still developing, but it’s already been through a number of milestones, and a lifetime’s worth of epileptic events. We can push the snowball back on path, but the path it made doesn’t disappear.

Susannah’s KAND didn’t miraculously reverse itself in the absence of mutant KIF1A; lost circuits haven’t spontaneously recovered, nor can she switch into an age-appropriate classroom. The changes she’s experienced are profound, and they are also limited.

Earlier I was privileged to stand in the Columbia Irvine Medical Center, where Dr. Bain introduced me to a child with Spinal Muscular Atrophy, a neuromuscular disorder among the most common genetic causes of infant death. That child benefited from a direct diagnostic journey and early ASO intervention; that child was walking, comfortably and confidently, across the room. It was, quite simply, one of the most miraculous events I’ve ever had the honor of seeing.

This gives me hope, that if we can redirect the snowball early we can better improve quality of life for our youngest patients. Our second pioneer Sloane is much younger; to promise or predict can be a risky venture, but at least I hope this early intervention will give her back more of her development.

So what next?

It’s an overwhelming question, because there is so much to do. But I’ll circle back to the theme of the pioneer.

This weekend I drove by a campground called “Pioneer/Fuller Park.” Seeing the theme of the year next to our Executive Director’s last name, I stopped there.

It’s beautiful; there are well-maintained campsites, trails, a railroad, and even some “rustic” cabins with electricity. And that’s very much the kind of image we, especially in the US, associate with pioneers: The legacy, the comfort that followed, the road that came after the path. We highlight the bravery but forget the reality of the forest.

For the actual pioneers, the ones our families actually represent, this place was very different. To reach this place would have meant blood, and sweat, and tears, and inconvenient poop. It meant suffering and risk, and for some poor souls, even death.

Luckily, Susannah’s not alone: Her helpers have been watching closely, trying to make each expedition safer than the last. We don’t know the ideal dose regimen for those who follow, but we’re finding out. As she leads us to the bleeding edge of medical science we’ll follow her path, trying to widen the trail for others.

We have a second pioneer following in Susannah’s footsteps: Sloane Hedstrom has begun her journey as well, and her mother Megan has been kind enough to share their experiences with the community.

But these successes also force the question of scaling. How do we facilitate these opportunities for the other families across the country that are a match for the ASO? And how can we help families in other parts of the world navigate their own countries’ regulatory framework? These are real challenges, but the fact that we face them speaks to how far we’ve come together.

With gratitude, in the Year of Pioneers.

Thanks so much for the text, Dylan. It is very clear on a scientific level and deeply emotional